Learn about the early history and special architecture of this famous street

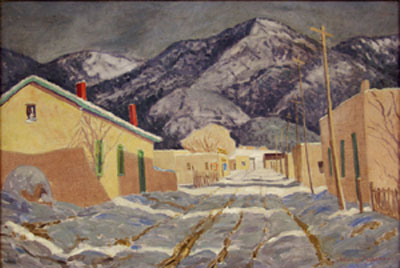

Winter Afternoon on Canyon Road

The unique mingling of fine art galleries with gracious adobe homes on winding, shaded streets is the essence of Canyon Road’s charm. Although it is just blocks from Santa Fe’s busy plaza, Canyon Road’s special quality arises from its history as a rural neighborhood of small farms scattered along an old Indian trail.

The oldest surviving houses on Canyon Road date at least to the 1750s, built as modest, two or three-room dwellings by early Spanish settlers. Each house was the center of a family farm that raised corn and wheat and vegetables on the fertile patches of land bordering the Santa Fe River. In those days it would not have been unusual to see a small flock of sheep being driven up the road on the way to green, mountain pastures deeper in the canyon.

Farming in this high desert climate always was a challenge. Shortly after founding Santa Fe in 1610, the Spanish built an irrigation canal above the river, parallel to Canyon Road. Still in use, this Acequia Madre, or “mother ditch,” brought precious water out of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to sustain crops, livestock, and people in the Canyon Road neighborhood. Present day visitors should take a stroll down shaded Acequia Madre Street (just one block south of Canyon Road) to enjoy the ancient stone-lined canal and the beautiful adobe homes that have depended on it for centuries.

From the earliest days of Spanish settlement, enterprising Santa Feans walked their burros up the old “Road of the Canyon” to gather firewood in the mountain forests. Late in the day, residents would see the burros lumbering back down Canyon Road, laden with impossibly large bundles of split pinon wood that were destined for delivery to customers in town or for sale in Santa Fe’s Burro Alley.

After the US Army arrived in Santa Fe in 1846, soldiers built a sawmill in the canyon and carted the lumber down Canyon Road to build Ft. Marcy, northeast of the plaza. The new fort marked the United States’ acquisition of New Mexico (and the rest of the southwest and California) in the Mexican-American War. As the capital of New Mexico Territory, Santa Fe would experience a new, American government, just as the old Santa Fe Trail would bring an ever larger influx of Anglo-American people and goods into this remote Spanish town.

Despite the changes going on around it, the Canyon Road neighborhood in the territorial era remained much as it had been for the previous century: a quiet farming community of Spanish families on the outskirts of Santa Fe. And so it would be until the birth of Santa Fe’s famous art colony in the early twentieth century.

Canyon Road and the Santa Fe Art Colony

Professional artists had visited Santa Fe on painting excursions since the 1880s. The region’s natural scenic beauty, Native pueblo cultures, and old Spanish villages provided abundant and exotic subject matter for painting and sculpture. Yet many of the artists who first chose Santa Fe as their permanent residence did so because its dry, clean air was a life-saving tonic for respiratory disease. Carlos Vierra, generally credited as the first professional Anglo artist to settle in Santa Fe, arrived in 1904 to be treated at Sunmount Sanitorium which was located at the foot of Monte Sol, the large hill above Canyon Road.

The first artist to reside permanently in the neighborhood was Gerald Cassidy who bought the house at 1000 Canyon Road in 1915. Cassidy had become familiar with the native peoples of northern New Mexico in 1890 when he entered a sanatorium in Albuquerque with severe pneumonia and six months to live. In 1912, fully recovered and newly married, Cassidy decided to relocate in Santa Fe with the intention of giving up his career as a commercial artist and devoting himself to painting full-time. A painter of southwestern landscapes, Native American genre scenes, and Native portraits, Cassidy spent the majority of his fine art career at the Canyon Road house and studio where he died in 1934.

Sheldon Parsons, a successful portrait painter in New York, arrived in Santa Fe in 1913 suffering a relapse of tuberculosis. Recently widowed, Parsons and his young daughter first took a small apartment near the plaza, but later moved into the Cassidys’ house on Canyon Road while the Cassidys were traveling abroad. In 1924, Parsons bought a tract of land at the foot of Upper Canyon Road where he built an adobe home and studio in the Spanish-Pueblo style. Known for his aspen-studded landscapes and scenes of old adobe homes, Parsons lived and painted in his Canyon Road home until his death in 1943.

In 1916, Santa Fe’s fledgling art community received a major boost with the arrival of William Penhallow Henderson, a successful painter and teacher, and Alice Corbin Henderson, a poet and associate editor of the influential Poetry magazine. The Hendersons came to Santa Fe so that Alice could be treated at Sunmount for advanced tuberculosis. While Alice was still living at the sanitorium, William bought a small adobe house on the Sunmount road, Camino del Monte Sol, just south of Canyon Road. In 1924, with Alice in better health, the Hendersons built a new house on adjacent property. Though Alice’s health forced her to resign from Poetry magazine, she maintained contact with her literary friends, entertaining such notables as Vachel Lindsay, Robert Frost, and Carl Sandburg in the big house on “The Camino.”

With their new home completed, W. P. Henderson converted the original house into his painting studio and the office for his construction business. Begun in 1926, The Pueblo Spanish Building Company created Spanish-Pueblo revival or “Santa Fe Style” architecture and furniture. A modern combination of Pueblo Indian and Spanish colonial adobe building styles, this look was being promoted by Santa Fe’s town fathers as a tourist draw as early as 1910. The members of Santa Fe’s art colony became early and enthusiastic promoters of the movement, usually building their own homes in the style. Indeed, the region’s indigenous adobe architecture was a major part of the aesthetic that had drawn them to live and paint in Santa Fe. Henderson was one of the most skilled of the artist/builders and was responsible for such surviving gems as the restoration of the historic Sena Plaza on Palace Avenue, Fremont Ellis’ last home on Canyon Road, and the Wheelwright Museum.

By 1919, Santa Fe’s growing reputation among east coast artists induced two friends from New York, John Sloan and Randall Davey, to take their wives on a cross-country excursion in a 1912 Simplex touring car. Well established artists in their own right (both had shown in New York’s legendary Armory Show in 1913, and Sloan was a member of a group known as “The Eight” which is credited as the origin of the “Ashcan School”) they carried a letter of introduction from their friend and mentor Robert Henri. Henri was an enthusiastic, if occasional, visitor to Santa Fe starting in 1917, but he did not embrace New Mexico with the life-long zeal shown by his friends. Sloan spent more than 30 summers in Santa Fe, living and painting in a studio on Garcia Street in the Canyon Road neighborhood. He returned each winter to New York where he painted, taught, and built a reputation as one of the nation’s leading artists. Davey decided to make Santa Fe his permanent home, returning in 1920 to purchase a large tract of land at the end of Upper Canyon Road. Included on the property was the old sawmill built by the US Army in 1847. With his wife and son, Davey restored and enlarged the building to use as their home. Davey also converted an old stone storage shed into the studio where he painted portraits, landscapes, and horse racing scenes until his death in 1964.

In a few short years, the presence of nationally known artists such as Henri, Sloan, and Davey had permanently established Santa Fe’s reputation as an important art colony. Their presence also made it inevitable that other artists soon would settle in to join them. The 22-year old Fremont Ellis moved to Santa Fe in 1919 “because of the interesting and important artists who were there.” The next year, Ellis joined with four other newly arrived artists, Josef Bakos, Walter Mruk, Willard Nash, and Will Shuster, to form Los Cinco Pintores or The Five Painters. All five artists were under 30 years of age when they arrived, and their work was strongly influenced by the Independent Movement led by Henri and Sloan, which sought to escape the conventions and limitations of academic art.

As young “independent” artists in the early 1920s, Los Cinco Pintores were enthralled with the artistic energy of Santa Fe, but still had a difficult time making a living. Consequently, the five friends resolved to build their own homes with their own hands despite that fact that none (except Bakos, who knew carpentry) had any building experience, especially with adobe. Securing land near W. P. Henderson’s studio, they started building small houses all in a row leading up the east side of Camino del Monte Sol. Will Shuster later recalled that he and Fremont Ellis were out building one day when Shuster noticed that Ellis’ wall was leaning precariously. Shuster ran to warn Ellis, only to turn around to see his own wall crumble into a pile of adobe bricks. In time, the five completed and occupied their homes, though some Santa Feans started referring to the friends as “five little nuts in five mud huts.”

Will Shuster, who probably suggested the move to The Camino, likely did so because his friend Frank Applegate had built a house there in 1922 and eagerly welcomed the Pintores as new neighbors. A sculpture and ceramics teacher in Trenton, New Jersey, Applegate first visited Santa Fe in 1921 on a tour to study native clays. After a week spent camping in the Cassidys’ orchard, he and his family decided to make Santa Fe their permanent home. Unlike Los Cinco Pintores, Applegate had studied architecture and was well equipped to design his own home and to offer advice to his young friends. In fact, Applegate quickly became one of the leaders of the Spanish/Pueblo revival movement in architecture. Along with the writer Mary Austin, he formed an organization that provided funds for the preservation of historic adobe churches at Chimayo, Trampas, Acoma, Laguna, and Zia. In 1925 he renovated an old four-room Spanish farmhouse just off the Camino, enlarged it and incorporated details such as balconies and cupboards from other historic Spanish homes in the area.

About the time Frank Applegate was remodeling his house, the cubist painter, Andrew Dasburg, moved into a new house on The Camino and became Applegate’s neighbor. Already established in New York art and literary circles (he, too, exhibited in the 1913 Armory Show), Dasburg first traveled to New Mexico in 1917 at the invitation of Mabel Dodge Luhan, legendary patroness of the arts and hostess of radical salons in New York and Taos. Dasburg’s wife, Ida, had organized the Provincetown theater group in Massachusetts and had been married to the radical writer Max Eastman, founder of the leftist periodical, The Masses. Between the Dasburgs and their neighbors, Alice and William Henderson, Mary Austin, and Lynn Riggs (author of Green Grow the Lilacs which became Oklahoma!), The Camino saw more than its share of literary, musical, and artistic gatherings. The group occasionally acted, sang, and danced in their own productions, often with Lynn Riggs on guitar and Fremont Ellis on drums. Neighborhood gatherings also included interested houseguests from “back east,” such as Willa Cather, Aaron Copland, Thornton Wilder, Edna Ferber, Ernest Block, and Martha Graham.

Olive Rush, an illustrator who studied with the master, Howard Pyle, had been spending time in Paris when her father asked her to accompany him on a western trip in 1914. In 1920, she returned to live permanently in Santa Fe. Rush settled on Canyon Road, buying the Rodriguez house, already a century old, and decorated it with Native and Spanish artifacts as well as her own artwork. Rush developed an interest in fresco painting and completed murals in the Ladies’ Library on Washington Street (now the Museum of New Mexico History Library) and the Santa Fe Indian School in addition to her home. A life-long Quaker, Rush bequeathed the house to the Society of Friends who still hold meetings among Rush’s art.

Artist Datus Myers and architect Alice Clark Myers, first arrived in Santa Fe in 1923 on a painting trip. Like so many other artists, the Myers found Santa Fe irresistible, and in 1925, they moved into the Canyon Road neighborhood where they remodeled an old adobe on the Camino. Datus Myers had studied painting and sculpture at the Chicago Art Institute where he met Alice Clark, one of the first female graduates in architecture. In the 1930s, Datus served as coordinator for the Federal Public Works of Art Project for New Mexico, and later taught at the Arsuna School of Fine Arts which occupied Mary Austin’s home on The Camino after her death in 1934.

Another victim of Santa Fe’s spell, Odon Hullenkremer’s, moved to Santa Fe from Toledo, Ohio in 1933. A native of Budapest, Hullenkremer undoubtedly was the best-trained academic artist in Santa Fe, having studied in Paris, Munich, Berlin, and Cairo in addition to his hometown. Settling into a home and studio at 820 Canyon Road, he built a highly successful portrait career. Known as an eccentric and a raconteur, Hullenkremer entertained a loyal following over cocktails almost daily at La Posada Hotel. However, the group rarely included other well-known artists, as he was a vocal critic of the Modernist Movement which dominated Santa Fe (and the Euro-American art world) at the time.

At the end of the Second World War, the Canyon Road neighborhood retained much of its rural character. Many descendents of the original Spanish farmers still lived in the aging adobe homes and some still farmed the small plots by the acequia and the river. But now, this centuries old neighborhood and its local culture existed side by side with a new, even avant garde, culture of fine artists, writers and musicians, many of whom were trained in Europe and most of whom were notable figures in the New York art world.

The Gallery Era on Canyon Road

Canyon Road’s gradual shift from a residential and farm road to a commercial district began in the late 1940s as a variety of businesses opened along its lower half-mile. However, in the post-war era , none of those businesses was an art gallery. Several were neighborhood-oriented services such as restaurants, bars, grocery stores, barber shop, dry-cleaner, pet supplies, photo studio, and even an Arthur Murray dance studio. Perhaps aligning with the existing art community, many other new entrepreneurs were craftspeople who probably sold their products directly from their home studios as well as to other retailers. Weavers, furniture makers, wood carvers, leatherworkers, potters, silversmiths, and jewelers crafted their wares in the old houses, barns and sheds along Canyon Road.

Of course, artists continued to move to the Canyon Road neighborhood, and many of them invited patrons and tourists to purchase work directly from their studios. Agnes Sims, best know for her studies of Indian petroglyphs arrived from New York about 1942 and moved among several homes and studios along the Road before acquiring the compound at #600. The Indian-portraitist, Louise Crow, worked briefly on the Road beginning in 1947, and Chuzo Tamotzu began his long Santa Fe career here in 1949. T. Harmon Parkhurst, one of New Mexico’s most important photographers and chronicler of local cultures operated on Canyon Road also beginning in 1949. In 1957, Fremont Ellis returned to the Canyon Road neighborhood after many years on his Espanola ranch, occupying the house designed W.P. Henderson at #553. That same year, Andrea Bacigalupa established his home and studio at #626. Andrea still occupies that home, making it the longest running studio/gallery in the history of Canyon Road.

With the Canyon Road art colony well into its second generation, it was inevitable to see a few businesses spring up that catered directly to the artists. The Hill and Canyon School of Arts opened at #1005 in 1947, and the first two of several art supply stores opened on the Road in 1953. One of those art supply stores, Artist’s Exchange Gallery, apparently also sold artwork, making it the first gallery to open on Canyon Road (according to city directories) in the post-war years.

The city of Santa Fe recognized Canyon Road’s uniquely beautiful combination of shops, studios, and homes in 1962, when it designated the Road a “residential arts and crafts zone.” This unusual legal status appeared to significantly boost the prospects for new galleries in the neighborhood. After the opening of Artist’s Exchange in 1953, the next new gallery did not come along until Agnes Sims opened her shop at #716 in 1959. 1960 saw two new galleries including one owned by popular local artist Hal West. No new galleries opened in 1961 but in 1962, the year of the new zoning, five new galleries appeared. Five more opened in 1963 and six more in 1964. Over the next decade and a half as many as seven new galleries opened each year. The 1960s and 1970s also saw the proliferation of curio shops, gift shops and antique stores but by the 1980s, fine art galleries clearly dominated commerce on Canyon Road.

Sadly for residents, most of the neighborhood-oriented businesses had disappeared by the early 1980s as real estate prices soared. Many of the old Canyon Road farmhouses were restored and enlarged or replaced, and vacant lots that formerly had been fields or orchards saw new residential construction as the Road became a fashionable place to live. A surprising number of very fine homes on Canyon Road lie just out of view behind adobe walls or tucked into the very deep lots behind the galleries. The residential part of the “residential arts and crafts zone” still is very much alive.

Canyon Road now is home to more than 125 galleries, boutiques and restaurants in the space of six short city blocks. Santa Fe is the second largest art market in the country, and the compact, walkable Canyon Road district includes more than half of the city’s total number of art retailers. The diversity of work shown by this multitude of galleries includes nearly every type of American art. A handful of shops sell historic art such as the work of the early Taos and Santa Fe art colonies, but most represent living artists. The work ranges from traditional realism and impressionism, to abstraction, expressionism, and contemporary realism. In addition to painting and sculpture, many galleries represent glass, ceramic, jewelry, and fiber artists, and a few sell historic and contemporary Native arts of the southwest including pottery, rugs, baskets, jewelry and paintings.

How can an out-of-the-way town of fewer than 70,000 residents support so many galleries? The answer, of course, is that people from all over the country—and the world—come to Santa Fe for its phenomenal selection of fine art. Come see for yourself. Canyon Road is not just a cluster of shops at the center of Santa Fe’s artistic community. It is an ancient neighborhood of historic adobe houses, manicured courtyard gardens, and hidden alleys, all interspersed with some of the country’s finest art galleries. It is one of the country’s most celebrated art districts; an art experience like no other.